Maine, the white star that burns from November, it rules a cold corner of sky. Here only short sentences and long thoughts can survive: unless you're made of north and given to long spells alone, don't trespass here from then ...

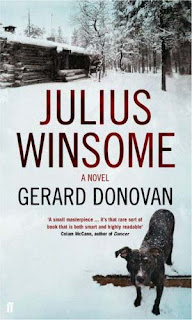

Love, loss and the isolated soul. As a devout fan of the nordic mysteries of Mankell, Theorin and company, Shade Point hugely enjoyed Julius Winsome. It is a story filled with crime, but not a procedural crime thriller in any sense, and the book is as much about the psychological reckoning of killing as it is about its pursuit or resolution. It lives in the sharp clearings of the mind that fight against despair taking hold. Therefore, although not marketed as a crime novel in this country as far as I can see, Julius Winsome would sit very comfortably with writers like those just mentioned, or Jan Costin Wagner, for example. There is a great deal of Cormac McCarthy to this story too, particularly those eerie mountain novels that stick around in your head for months after you've read them. If they haven't already, the Coen Brothers should read Julius Winsome. They would have the eye I think to take this dark, deeply compelling piece of backwoods mountain noir and make it into an absolutely superb film.

Julius Winsome lives on his own in a cabin in the Maine woods. He is fifty one, and has known no other home. His father has died, leaving him the cabin, thousands of books, an Enfield rifle and an emotional inheritance of two World Wars. When required, Julius has the vocabulary of Shakespeare's England to describe the invisible world he lives in. He seems to have managed this existence reasonably well until the arrival of Claire. Or, more correctly, until the leaving of Claire. Like a figure from folktales, she simply emerges from the woods one day. She hails from the nearest town, but this nearest town is far to travel and inhospitably so, and the simple act of her turning up seems slightly unreal, magical. She strikes up a relationship with this abandoned soul Winsome and together they even get a dog to keep him company, which they name Hobbes, and for a short time there is a new light in the dark cabin. And then, as soon as she has arrived it seems, Claire is gone. Julius is plunged back into invisibility, his heart aching, but back into the comfort of routine, and with Hobbes, a new togetherness to carry on with - to somehow assuage the grief he feels at her leaving.

That is, of course, until someone shoots and kills Hobbes. What happens next, I'll leave you to watch through your own fingers in dismay.

The two great triumphs of this book are the narration, by Julius himself, and the evocation of the Maine wilderness. As we get to know Julius, the more complex he becomes, and yet at the same time, the more innocent. Maine, particularly as winter feeds in, changes from a place of wild flowers and trips to the town for coffee, to impassable snow and dread darkness, hunters in the woods, and in Julius Winsome, blood and terror. Somewhat like Lieutenant Glahn in Knut Hamsun's masterpiece Pan, Julius begins to hunt himself in some way, to unravel before our eyes. The dead Hobbes, buried under the snow by the cabin, continues to live fiercely in Julius, like some kind of dark beacon dragging him further and further out. The symbols and markers of Winsome's life are not those of the 'real' world, and when one existence spills over into the other, when loss becomes unbearable, there is big trouble.

This short, dark, menacing book deserves to be much better known. It is written with a poet's eye for detail, and a hugely successful imagining of the interior landscape of Julius Winsome's psychology, as well as the alternately idyllic and hostile woodlands. It renders perfectly the seemingly indefatigable freshness of loss of love, such that with each new day it seems no more distant than the day it occurred, and no more understandable. When it comes, the action is unflinching, terrible and violent, and this steadily more ominous story has both the drive of a strong thriller, and the unrelenting investigation into the burdens of being human of those Scandinavian stories I mentioned at the beginning of this review, whose characters and settings are themselves 'made of north'. Here is a book for the dark places, the dark woods, and for what happens when the darkness bursts out from them, inchoate and despairing, to live for a brief time in the light.

The absence of someone comes like a new season, first only in pieces: you see the absence of them long before they leave ...